Where is wonder in computational neuroscience?

Updated:

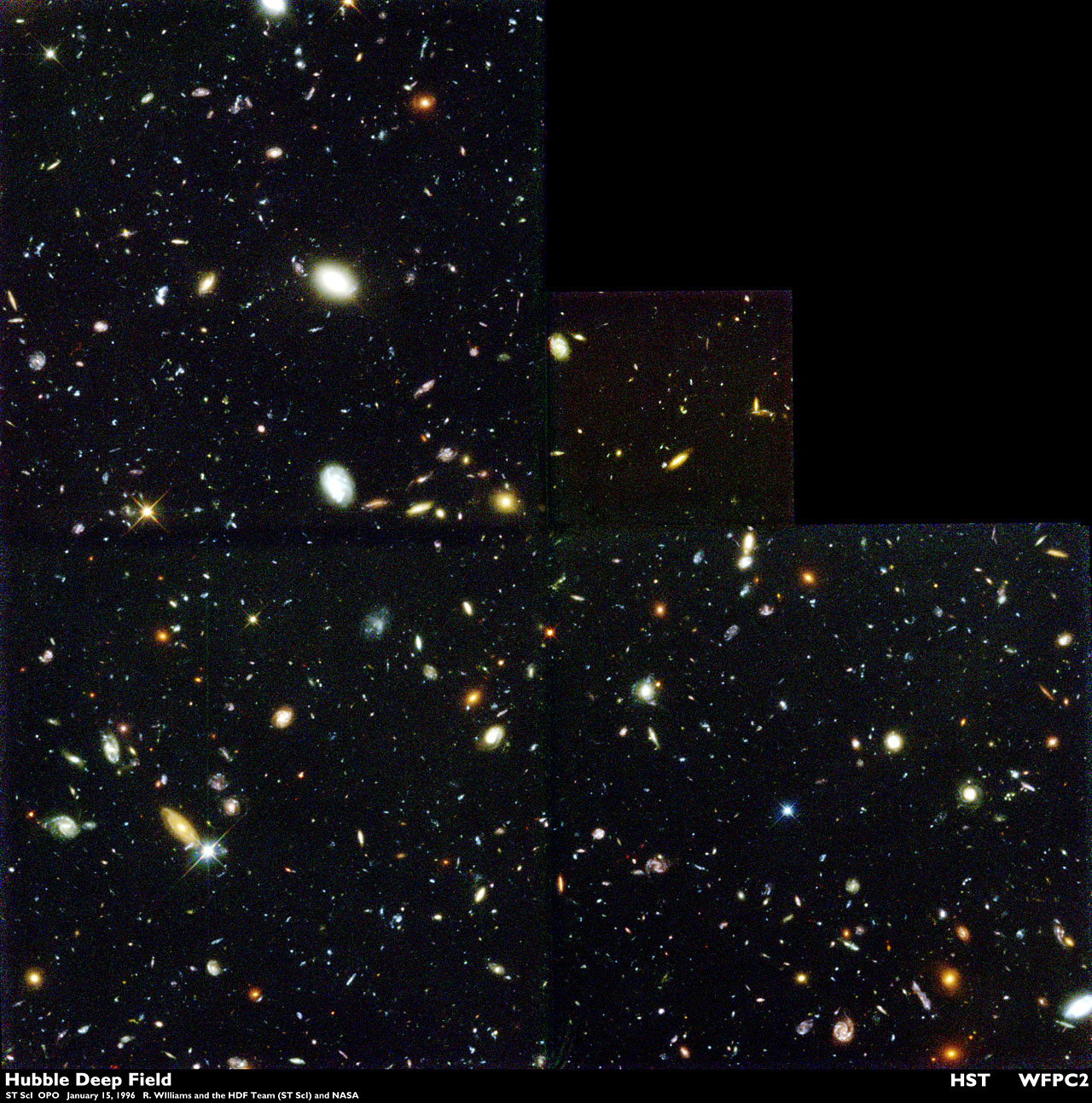

If you’re reading this, then I know that you’ve experienced a true sense of wonder at least once in your life. Wonder astonishes. For me, wonder is closest to awe. It accompanies revelations, usually visual, that my own experience and moment in time is astonishingly minute. I’ve experienced this staring at the stars on many occasions; on viewing the Hubble deep field for the first time; on gazing over layers of strata in the American Southwest.

I’m not sure humanity would pursue science if no one felt a sense of wonder. Reality— its unimaginability, its intricacy— is wondrous, and this is what draws us to know it as best we can. I t may be difficult to describe wonder’s necessity for science better than, of course, Einstein, who wrote, “The fairest thing we can experience is the mysterious… He who knows it not and can no longer wonder, no longer fell amazement, is a good as dead. A snuffed-out candle.”1

But what exactly is wonder? When do we feel it? I’m compelled by the idea that wonder is reliably felt when confronted with the true scale of the unknown. Unknowability is key to wonder. Not abject unknowability, the “unknown unknown”, but a known unknowability. We learn, in some new way, that the world is vaster and more marvelous and complex than we had the capacity to imagine.

“Once we lose our fear of being tiny, we find ourselves on the threshold of a vast and awesome universe which dwarfs—in time, in space, and in potential—the tidy anthropocentric proscenium of our ancestors” – Carl Sagan 2

The requirement of an unknowable vastness—of time, space, or potential— seems at odds with the goals of science. If we seek to understand, and wonder requires unknowability, does understanding diminish wonder? Does science kills wonder by explaining things away?

I say no. Wonder first requires discovery. Without science, these vastnesses would remain unseen. Wonder and explanation are best described as in a dance. At times they are in opposition to one another. But they are co-dependent, and give rise to one another.

Should scientific disciplines seek to produce wonder? I don’t think many would say “no”, here. To many, including the religious, the feeling that the universe is a marvelous place is what makes life worth living, and if a discipline has the opportunity to instill wonder it should seize it.

On the other hand, though, pursuing wonder is at odds with many traditional ways of doing science. Compared to other aims of science, producing wonder stands out by not requiring explanation – or is even at odds with it.

Producing wonder is rarely a consequence of modeling and explanation. Consider the Hubble Deep Field or Pale Blue Dot images – these are not explanations of previous phenomena, nor were they themselves the end products of traditional scientific study. They emerged from it, but were not the goals of their sciences. (The Hubble Deep Field was not an approved proposal, for instance, but a use of director’s discretionary time. And what new knowledge was gained from training Voyager’s camera back on Earth?). Yet despite their explanatory emptiness, these provoke wonder and inspired generations of scientists. Only after their creation did these windows on deep space induce curiosity about what they revealed.

The dichotomy between wonder and explanation, and yet their mutual requirement, surprised me when I first encountered it. In my discipline, “to explain” is the highest goal. We have normative explanations, evolutionary explanations, computational explanations. Computational neuroscience takes for granted what deserves explaining – animal behavior, for instance. But by focusing so much on explaining everything, what new wonder do we uncover?

What would a computational neuroscience look like that aimed to produce wonder? What are the Pale Blue Dot and Deep Field images of neuroscience?

-

from The world as I See It (1956), quoted in Krista Tippet, Einstein’s God: Conversations about Science and the Human Spirit (2010) and again in “Like Two Black Holes Colliding”, Explode Every Day: An Inquiry into the Phenomenon of Wonder (2016) ↩

-

Pale Blue Dot (1994), quoted in Rachel Sussman, The Oldest Living Things in the World, quoted again in “Unknown Unknowns”, Explode Every Day: An Inquiry into the Phenomenon of Wonder (2016) ↩